—by Tony Menelik Van Der Meer

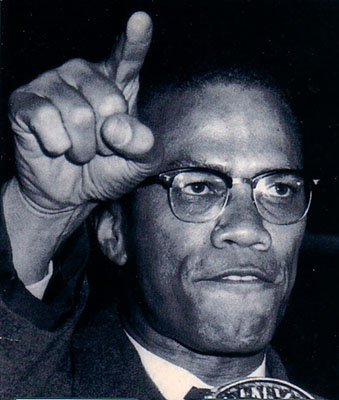

Malcolm X

The 40th anniversary of Malcolm X’s horrid assassination was commemorated February 21, 2005. For many African Americans and a growing number of non-African Americans, the ideas Malcolm X addressed represent the essence of freedom, justice and equality. If he were alive today, Malcolm would be the poster child for dissent, free speech and a leading voice for peace, social justice and human equality. While Malcolm X’s life can be seen in several major transitional stages, white America in general has seen him as the black firebrand accusing the “white man” of being the “devil.” For African Americans that was not much of a stretch. Yet, the stage of Malcolm’s life that is often neglected is his post Nation of Islam period, when he became an independent thinker.

It is commonly acknowledged that Malcolm X frightened white America and quite a few “negroes.” What was it about Malcolm that upset people in this way? Did his bold and direct talk of race do it? Did he make sense to those black masses that were “sick and tired of being sick and tired?” Did he speak truth to power?

Growing up in Harlem, I lived in the shadow of Malcolm X. My older brother and his peers as teenagers loved and often talked about what Malcolm said or did. While I never personally met or saw Malcolm X, his political associates, Queen Mother Moore, Yuri Kochiyama, Max Stanford, Askia Touré, Akamal Duncan and many others who were close acquaintances of mine, helped me understand why and how, as youth, my brother and his cohorts had such high regard for him.

Malcolm X gave them dignity. He demonstrated by his experiences and example that human beings can grow and develop. He was an example that one must take responsibility for his or her destiny, as pointed out in his autobiography, even if black people can’t live as men and women, they should at least die as one.

What is critically important is how Malcolm X’s direct and plain style of addressing substantive issues—along with his courage and dignity—even today, appeals to a broader audience than African Americans and other people of color. This shouldn’t be a surprise considering that his book, The Autobiography of Malcolm X, sold over 3 million copies worldwide. When Malcolm X spoke at the Oxford Union debates and at the London School of Economics in England to very intellectually astute crowds, his majority white audiences were mesmerized by him. In my travels to Germany and Holland, I too had witnessed whites who were able to see a perspective of Malcolm X as a man of humane courage, dignity and value.

I also observed how students enrolled in my Martin and Malcolm class, both white and black, reevaluated Malcolm after critically examining his speeches and ideas. Many of those students who had little or no exposure to Malcolm X other than acknowledging that he was for “violence,” began to question their educational process and sources of information.

Ossie Davis, the beloved actor and civil rights activist who recently passed away, asked in his famous eulogy of Malcolm X, “Did you ever listen to him? Did he ever do a mean thing? Was he ever himself associated with violence or any public disturbance?” As a Muslim convert, Malcolm X imposed strict discipline upon himself in order to uphold a set of values that required one to be upright and righteous. Thus, the conversion of Malcolm Little to Malcolm X was the beginning of a whole new person. It was this new person in Malcolm X about whom Ossie Davis spoke.

Then there is another transformation of Malcolm X, who upon being forced to leave the Nation of Islam travels to Africa. Then to make his Hajj to Mecca, he grows and develops more into an independent thinker. It is this stage of his life that Malcolm is at his sharpest even though he is experiencing the most tense and stressful period of his 39 years. This period of Malcolm X’s life has much to teach us about ourselves and the world we live in, both now and then.

Ossie Davis put it best 40 years ago, “…what we place in the ground is no more now a man—but a seed—which, after the winter of our discontent, will come forth again to meet us.” Now, 40 years later, the dust cleared, we can reflect on what is Malcolm X’s meaning to history. Today, Malcolm’s voice still resonates and he still meets us—as we contemplate how to bring about real peace, freedom, justice and equality to our world.