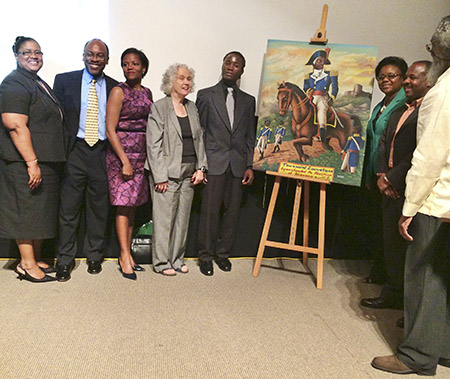

From left to right: Gladys Joseph of the Haitian Consulate, HAAM’s Charlot Lucien, State Sen. Linda Dorcena Forry, Prof. Patricia Hills, Pascal Michel and his painting, Marie St Fleur, Nesly Métayer, State Rep. Byron Rushing at the June 17, 2014, event in BPL Copley Square —photo Jacques Chéry.

Poet Patrick Sylvain at the May 27, 2014, event in BPL Mattapan Branch —photo Nixon Léger.

A partial view of the audience at the May 27, 2014, event in BPL Mattapan Branch —photo Nixon Léger.

State Senator Linda Dorcena Forry at the June 17, 2014, event in BPL Copley Square —photo Jacques Chéry.

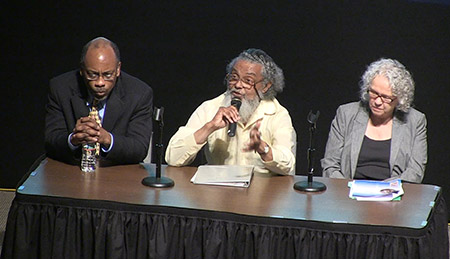

From left to right: HAAM’s Charlot Lucien, State Rep. Byron Rushing and Prof. Patricia Hills at the June 17, 2014, event in BPL Copley Square —photo Jacques Chéry.

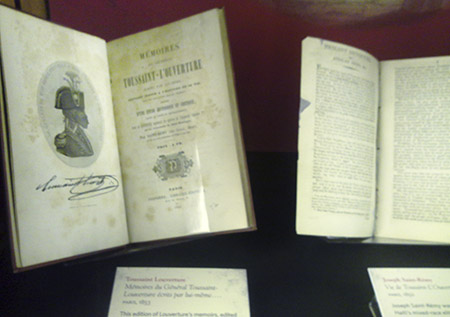

Ancient books on Toussaint Louverture in BPL’s Rare Books collection.

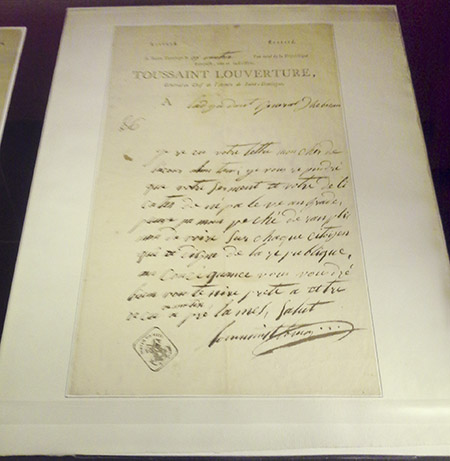

Original manuscript letter from Toussaint Louverture in the BPL’s Rare Books collection.

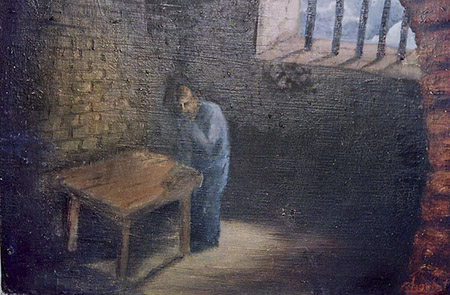

« Toussaint Louverture à Fort de Joux », peinture de Charlot Lucien.

« Toussaint Louverture », peinture de Pascal Michel.

About Toussaint Louverture…

Two hundred and twenty years ago, in 1793, Toussaint Louverture, who at the age of fifty had spent thirty years of his life in slavery, rose in the ranks of the African slaves of the French colony of Saint Domingue (now Haiti) as a fierce abolitionist and a brilliant military strategist. For many years he pursued a relentless military and guerilla war against the Spanish (March 1794), the British (1798) and the French armies (1801–1802), systematically dismantling the slave structure that had close to 500,000 Africans in bondage for about three centuries. His quest for freedom for the African slaves later took a shift when he moved to assert the autonomy of the French colony under his sole authority, prompting Napoleon Bonaparte to send between 1802 and 1803 the most powerful armada with objective to reconquer the rebellious colony, deport the leaders of the Haitian revolution and reestablish slavery. Toussaint was later captured in June 1802 and sent in exile in France where he died in April 1803. His lieutenant Jean-Jacques Dessalines and his officers continued a fierce battle against the French troops, which resulted in 1804 in the independence of Haiti, the first black republic in the world and the second republic in the Western Hemisphere after the United States.

Toussaint and the US Connection

During his ten years at the helm of Haiti’s affairs, Toussaint interacted with President John Adams through US Consul Edward Stevens with the goal of getting weapons to conduct war against Great Britain and France. However, in a shift of policy, Adams’ successor Jefferson openly plotted with Napoleon to contain the spread of Toussaint’s revolution. The US would not recognize Haiti’s independence for 60 years.

Toussaint became the object of admiration or intense scrutiny both by abolitionists in the North and slave owners in the South and his actions inspired generations of abolitionists and slave rebels in the Virginia and Mississippi areas during the 1820s and 1840s. Charismatic slave leader Denmark Vesey, who started a slave rebellion in Charleston in the 1820s, is reported to have frequently used quotes and readings on Toussaint Louverture to keep his followers motivated. Similar accounts are reported by Alex Haley in his masterpiece “Roots.”

Since then, Toussaint’s name has been consistently referred to by US historians and the most famous leaders of the US abolitionist and civil rights movements, black and white alike: Frederick Douglas, John Brown, Senator Charles Summer, Wendell Phillips, Alex Haley, and Malcom X among others. Such testimonies can be found in speeches by Douglas at the World Fair in Chicago (1893) or Anti-Slavery Society president Wendell Philips in New York (1881) and Boston (1884).

Modern historians—Alf J. Mapp, Conor C. O’Brian, Madison Smart Bell, Laurent Dubois… to cite a few—acknowledge today that Toussaint’s victories over Bonaparte’s armies had far reaching implications. They contributed to the emancipation of blacks in the world, inspired abolitionists worldwide and helped change dramatically the geographic make-up of the US by doubling its size in 1803. Indeed, after loosing some 40,000 troops in Haiti, Bonaparte abandoned plans to claim France’s Louisiana territories previously acquired from Spain and sold them to the US for about $15 million (today’s currency). About 827,000 Square miles were added to the US territories, almost doubling the size of the states, making this transaction “the cheapest real estate bargain in history.”

A case for a memorialization in New England…

The New England connections are overwhelming and the case for a meaningful memorialization of Toussaint is strong. It is more than the connection to towering New England abolitionists or key politicians—evidenced by materials found in the Boston Public Library’s rich collection of rare publications on Haiti. Precedents regarding such memorialization also abound: Florida has its Louverture memorials (Miami, Delray Beach); monuments have been erected in Cuba (Havana), Africa (Benin…), France (Paris, Pontarliers), Canada (Quebec) to cite a few. Interestingly, such precedents also exist in Haiti where South American liberator Simón Bolívar, abolitionists Charles Sumner, John Brown, Martin Luther King, and Harry Truman have major arteries and Boulevards named after them.

The memorialization of Toussaint would also honor the large Haitian-American community in Massachusetts, some 80,000 strong, and recognize its important civic and intellectual contributions to the state: dozen sound social and civic organizations, a vibrant media sector, an annual Haitian Unity Parade that usually gathers thousands of participants, a dynamic political presence with leaders such as former State Representative Marie St. Fleur or Senator Linda Dorcena Forry.

Toussaint’s relationship to abolitionist New England begs for a more visible and lasting memorialization. A street? A monument? A building or reading space in a public or academic setting? Let us initiate a thoughtful process. Still, beyond the physical memorialization, a more profound, historical one is overdue. Let us strive to update the social sciences curricula and history books, from America to Africa, and insure that future generations learn of Toussaint, the abolitionist from the Caribbean Islands and his role as part of their own history.

Charlot Lucien is the founder of the Haitian Artists Assembly of Massachusetts, a member of the Haitian-Americans United Inc and the president of GRAHN (Groupe de Reflexion et d’Action pour une Haïti Nouvelle) in New England.

Anne Anninger is a former Philip Hofer Curator of Printing and Graphic Arts at Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.