Poems by Anna Wexler

Fluid precaution

Most beautiful baby born

into a laboratory maze

of uncalculated risks

your mother is waiting

behind an alien sign:

don’t touch, breathe

or absorb this body.

It knows too much.

From the move-sanrising up

your milk was spoiled

as her grief was split

into every multiple of fear.

Still you come loving

her aching breasts

and continents of softness.

We know how to cover this child

with heirloom blankets woven

out of moonlight

but the old prayers

are shadows under the water

moving beyond sound.

May their syllables

return and teach us

between life and the endless

figures of its inversion

is the sweet dark moan of labor

humming across our bloodlines.

The Following Dream

I listen under

the thin cadence of your disbelief

where your voice begins.

All the lwa walked beside us.

From the deep spring

they spoke to us in echoes.

Without knowing you have forgotten

I remind you.

You keep talking

while my body listens.

There are always reasons

afraid and hungry

they believe

spirits seal every footprint

make the corn come gold

their blood quicken.

I wanted to drink

in the deep spring

where your voice begins

but you deny your hunger.

Which lwa

put basil in my dream

where I was lonely

green and pungent leaves

to sweep my body

clear of sorrow?

—Anna Wexler

Poem by Joe Davis

Joseph’s coat

A man sleeping in front of the cinema next to bassin de l’Ourq in Paris. —photo by David Henry, May 2001

What conspicuous nature operates

the thin apertures of belief and omission

that represent the truth

facts and strange companions press between

the ten thousand sheets

fingerprints peeling from the long record of days

page after page of history

and philosophy

and the footprints of councilors and ants

step by step

one by one

tooth by tooth

termites and angels slide out of heaven together

in big four-doors

they drive nice cars down through the high walls of paradise

where living things cavitate and disappear

with articles of faith

down in dark rooms of the obscure camera

where good friends and gathering godgs

return the fruits of flesh and blood

but it is apple-flavored

one time slash and burn operations

taking out Brazil for cheap power

and cold-blooded pleasures

there are ten thousand terrorists in paradise.

So now I take Joseph’s coat

many souls folded in the collar

I draw my breath in pockets cut from skin and clods of Earth

and sing my lovesong for the dead

long, departing lines press the air

like the thick of flies feeding on the carcass

I teach the grains of sand to sing my song

and pour them into the silences of Heaven

when I lift my voice it is the seeds of weeds and clouds of dust

and when I lift my hand it is a black flag

and all the princes of darkness stop to grind their teeth

familiar corpses wait at the grave

like racehorses grazing in their fields at night

stand by each narrow gates and call them out

by all their secret names…

I go riding back and forth from the fat belly of Egypt

in the big green ship of Allah

sucking up infections from the legs of frogs

and dare to read the dreams of an evil genius

I take them up in plastic bags and set them out at night

soldiers in the covers of darkness

cracking in the wind

like voices of wisdom in the radio background

Heaven reaches down to lift her dress

giants and mastodons drop to their knees

great stones break apart on the tables

when I lift my glass the oceans pitch and curl

clouds of dust and seeds of weeds

they are robes

the leaves of the trees and the blades of grass

and I go down again to lie beside the Nile

and the princes of darkness can have the air.

—Joe Davis

Poems by Bryan Sangudi

mellow mood

when mellow mood has got me

and from it i just can’t break free

i pick up a pen and scratch words on paper

trying to bury my thoughts until later

when i read those words to myself again

remembering why i wrote them,

remembering the pain

i thank the most high that the pain didn’t last

i remember the words—hurt only came to pass

it is not

it is not the recorded events in history i think of

it is the unwritten side that really affects me

it is not the police nightsticks which hurt

it is the hatred in their fake laughter and handshakes

it is not what they did

it is how they feel

beware you educated ones, beware

while they teach you what happened

while they teach you what to do

while they teach you what is to happen

do not ever forget how to feel

no one can ever teach you that

it is something you have to remember not to forget

history

history repeats itself

and our history is bad

but is it really all bad

or is it just what some want us to believe

and even the “bad” moments comparatively good

who, i ask, who would rather torture the innocent

than fight their struggle of liberation

who would rather scorn the poor

than build wealth with them

who would rather swim in the pain of their suffering

than dance in the joy of their songs of freedom

people who would rather steal all than share, that’s who

people who slaughtered the innocent, giving reasons why

to civilize, christianize, and enforce order are the excuses they gave

but i refuse to learn and be baptized in evil ways

i am one who didn’t wait for book to teach me right from wrong

i was born communicating with the most high

and i’ve known all along

the path to the future

i see it clear as day

put down your weapons of destruction and watch me move,

soon you too will see the light and get into the groove

—Bryan Sangudi

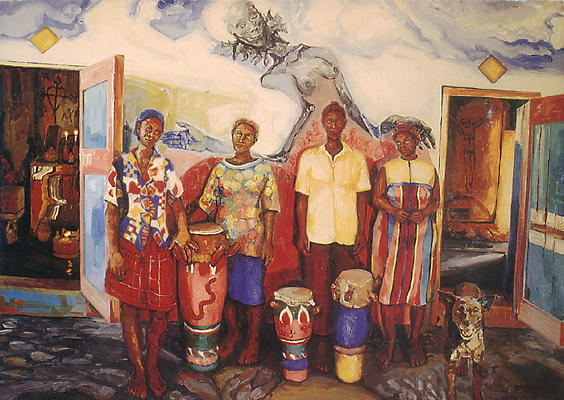

Poems by Marilène Phipps

(Extracts from Crossroads and Unholy Water)

Aunt Frances the Pianist

In the rough rivers where she swam,

Aunt Frances liked to anchor herself

with one hand to a rock, then wave

to us children lined up along the banks.

The water slapped and sucked

the unprotected parts of her body:

petals of rubber daisies on her cap

seemed like bouncing tentacles of one-eyed creatures

positioned in surveillance around her small head;

snorkel and mask channeled her sight and breath;

hard-meshed nylon cups held her breasts

within the bathing suit; black

flippers extended her bunioned toes.

Long-limbed, squared and no butt,

she waddled. No curves on her body

except for breasts which once had fed

her only son (born deaf) who spent his time

intent on solving mathematical equations

or reading out of stacks of comic books

about superheroes. She spoke little,

smiled often, but her teeth were false.

At night the teeth sat in a water-filled glass.

Her husband had his own bedroom. We found her

exotic, foreign… our American aunt!

(A noted pianist once!)… shy to show photos

of her parents’ house, a sister, a cardinal

in a high tree, a field of wheat.

The only voice left from her home was her piano.

Her husband, the ear-nose-and-throat specialist,

always left the house when she played.

Music also made the two dogs howl

and howl continuously at her side,

every time, until she gave up playing.

For years the stilled piano remained

planted on the front room’s green mosaic floor,

used as a table at Christmas

to display gifts. She drank.

For years. Rum cocktails

at noon. Rum cocktails

alone. Rum cocktails

always. In the bathroom,

thin towels were always damp;

tropical fungus blistered

the walls. And all the while

the dogs at her feet.

Scratching. Grunting.

Wheezing. Getting old.

Dying. Replaced

by the same.

Elzir’s Advice

As soon as your husband is dead, slap him

and cross over his body three times!

This way you let him know you

are no longer friends. When he’s in the coffin

sprinkle his body with sesame seeds and

attach lots of pins on his lapel. Spread more

sesame around his grave mixed with broken needles.

That’ll give him something to do!—trying to thread

tiny seeds with broken needles—and

keep his mind off you.

Wear red panties and nightshirt—they’ll be like stoplights.

He won’t be able to climb over you at night

(you don’t want that, do you?).

Everybody here knows the dead have power.

He is bound to miss you. He was used

to your company—he’ll want to visit.

Hell! He might want to take you with him!

At his funeral,

you’ve got to cry loud and clear!

You do not want to humiliate him—let people

know, by the way you cry, that he was

a good man, respectable and loved. That

is the only reason we are so noisy at funerals!

Not for the dead. Why, there is nothing to regret

about this earth!

Caribbean Corpses

for Allen Litowitz

Midday. The family sits behind Emmanuel’s corpse.

His adolescent granddaughters, self-conscious,

their bursting nipples squeezed in white

Sunday dresses: three child brides for their grandfather’s

funeral. Sweat gathers and tickles in the crease

behind their knees. A veil of mosquito netting

is spread over the body in the open casket.

On the wall above the coffin, a porcelain blond

Christ points to his own bleeding heart.

Green mildew lines swerve down Saint Peter’s

whitewashed walls in Pétionville. Lizards copulate

behind the old Way of the Cross. One granddaughter

wants to keep this last image of her grandfather:

nose with folded wings which seemed to guard his face;

teeth long and yellowed, some old molars, rotting—

it’s almost a relief his lips have now snapped shut.

Her eyes make out his hands—fingers like her father’s,

who just happened to cast a glance at his mother

because his ex-wife—number two—is walking up

the aisle, dressed in white lace. Emmanuel’s old bride had

already spotted her. Today she must mask

her joy at having won her son back since his divorce.

When she does not nag about his failed marriages,

she complains about his now dead father—she says

Emmanuel still masturbated at eighty-eight and

it’s his own fault if he died. Oui Maman, her son says;

“the doctor thinks I starved him but it is not so;”

Oui M’man “…couldn’t come to the table… has no strength…

a hypochondriac! It’s his own damn fault!” Oui M’man.

Mosquitoes buzz in circle formation over sweaty scalps

of women smelling of too much Frangipani or Florida Cologne.

Dressed in lace, satin, taffeta, they fan themselves

with one hand, slap flies with the other.

Men, in dark suits, repeatedly wipe their foreheads

and the back of their necks; so does the government’s

representative sent to pay homage to the years

Emmanuel worked as a state civil engineer.

People searching the ceiling for air vents,

wondering who the hell planned this building like that,

find Saint Theresa’s eyes are also looking up to

heaven while Saint Lucy carries hers on a plate.

Late, just off a plane from the U.S., Emmanuel’s

daughter arrives at the portal. She enters

with a long wail. Her friends turn bored

and bloated eyes from either side of the aisle. She runs

to bury her face in her father’s veil. Her mother’s jealous

displeasure is distracted by a commotion

in the next chapel where a new widow

screams from the top of her lungs there is black magic

in this place, the Priest is a God-damn-

black-ass-Zombie-maker-husband-thief!

It’s the wrong fucking corpse in the box.

Now something new is coming slowly down the aisle:

a white three-legged bitch with yellow eyes,

its head low, tail tucked close between the hind legs,

drooped tits brushing the mosaic floor. It pauses,

looks people briefly in the eyes, finally walks

up to where Emmanuel lies. A breeze almost

lifts the veil, but the dog drops a paw on it just

in time, pulls it all off into a pile, thinking

Ha! Human beings and their white veils! Give me a break…

Sits on it, yawns, scratches its fleas with a vengeance.

Cousin Thérèse

Clocks, too many clocks, ticking.

I would like back the first clock

my mother gave me, with gold vines

and torsades swerving like Thérèse’s hair

about her face.

“Go, go down deep…”—she lets

out of water-filled bags gold fish

into the backyard pond. They reach for the dark,

then resurface for a bubble of sun.

Cousin Thérèse helps people die.

At the hospice

she tells the sick how Jesus

stood in water to be baptized

before he could one day walk over it.

In small bouquets, she brings them daisies.

Petite, unfailing, feminine

she sits by the dying.

She knows them from their profiles—

horizontal, ashen traces, printed along

the white echoing strips of cotton sheets.

Which one has clutched her rope-braid

wanting to secure his descent?

How many hands have taken to their graves

the fragrance from her finger tips?

Whose eyes parched by the bland room

still stare at her on the windshield

while she drives home for supper?

Life moves to unexplained fragments

of music.

I miss the laughter

of the old woman who gave us candy

in a blue room overlooking the bay.

She told us those who do not pray

before sleep do not fly in their dreams.

From bullets, knives, or ropes around my neck,

I have lived many nightmare deaths my skin

remembers long after I awake.

“I can help you die too,”

she whispers to me.

Yes, Cousin Thérèse, I know,

with your smile only, you can make me

plunge,

care not.

Haïtian masks

I. Childhood

I thought that death had made him arrogant.

My mother had hung her father’s

death mask where I had to look up high

to that hairless white plaster double,

the only face of his that now seems real,

sealed eyes, lips thin, tight.

High forehead leading to a rough dropping edge. No skull.

Surrounded by Mother’s painted self-portraits

he seemed the rigid heart of a glitter-dappled corolla,

idealized, pained petals,

one of which was her gold-framed mirror.

There she scrutinized her paling face

twice a day, arching bright reds,

black lashes, geisha-like powder.

I grabbed that centerpiece

once for Mardi Gras

and ran with it

hearing mother trail after me with a distinctive howl.

II. Adolescence

for Guslé Villedrouin

Pour water on my head

so the sun might glimmer

on me. It is for hope that God

will pull them up by the hair to heaven

that Hare Krishna followers dance in the cold.

I saw my godfather’s face

on the newspaper’s front page, large,

written out as the rebel, caught

by the blue-vested Macoutes.

He had a new mustache.

I missed his gaze, deep chestnut.

Fat fingers gripped

his young man’s hair

as if it were a big knot

at the top end of a loose rope, his neck

cut off.

III. Womanhood

for Yves Moniquet AKA Delta Acruz

You had fathered me into hope

after nested clawed creatures

gnawed at my heart.

I pull you from the moist shallows

of the bed. Your head

like a fading bouquet your two hands

hold at the throat

is offered on my lap, past use, past hope.

“I am afraid” you whisper with open eyes

in the early morning glare

when the parched burning in your lungs

sucks the last bit of breath

from your recurved tongue.

Now, I move through moon-blanched visions.

Fervor has the color of alizarin for a gravedigger

who wants to keep you from being thrown

into the communal hell-hole of those too damn poor

to afford a little plot of eternal peace

in the crowded downtown cemetery.

I come to get you out, reclaim you,

you, for many months, furrowed in the grave.

I am greeted

by another face

and a smile without lips.

A soundless wave of gleam-corseted cockroaches

scurries down the two sides of your coffin.

Through weeds, they run away with your image.

The Bull at Nan Souvnans

I.

He was brought in yesterday

as an offering

for today’s Easter Sunday rites,

pulled by a rope

to these ancient and sacred grounds of Souvnans,

then tied by the acacia tree, all day, unfed.

Now, noontime, he lies and waits,

his root-like legs make dust enclaves

next to his sweat-furrowed flank.

He no longer shows annoyance

towards the scrawny chick hopping

around and pecking at his flesh.

“PA MANYEN L

SE LANMO W AP GADE!—

DON’T TOUCH HIM!”—

a voice threatens us—

“It is death you’re seeing!”

The bull stands up.

His nostrils reach, breathe in

towards the growing crowd.

Hands with a purpose, now untie him,

take him to another tree. He goes,

as if for his familiar fields.

“DON’T TOUCH HIM!

DON’T YOU KNOW!?”

II.

Now the bull is resisting!

All legs stiffened,

he won’t get close to

this tree! Swiftly,

ropes are wound at the base of

each of his horns,

crossed

on his forehead,

and yanked

on either side.

They force the flat part of his broad face

against the tree trunk.

Men dragging at his tail keep him

aligned. He can’t move.

He can’t see beyond the tree bark,

the roots or his hoofs.

Midday sun stings him.

A man straddles him, he can’t move.

He hears all

where he can no longer look.

The bull trembles.

The ropes are tugged tighter

and fastened behind the tree.

A shiver vibrates down his spine,

his entrails deliver their moist soil—

he defecates. Someone in the crowd… laughs.

“METE GASON SOU NOU!—

WE MUST BE VIRILE!”, Rene

Master of Ceremony—calls out,

flourishing his machete

to the Ounsi—handmaidens of the Gods—

gathered around him in white dresses.

They respond and wave their machetes,

symbolic wooden ones. Now Rene

shakes hands with the executioner

over the stilled body of the bull.

“LET US BE MEN!”

III.

The dagger and the screams

start in the same instant.

Deep, long, helpless bellows;

thick, gray tongue extended,

recurved, stiff and drooling.

The knife misses its aim

for the spine, at the base of the neck,

pulls out and stabs again.

Again, twists, pulls out and stabs again.

Blood gurgles, gushes out,

drawing a red web on the bull’s back

live lava’s hands about to blanket

the city in silence.

The legs falter

then regroup.

The dagger thumps down again.

Again, the legs falter and fold.

Like a great ship sinking,

the rear lowers first—his head

being stuck at the tree.

But he stands up again!

“TO THE THROAT!”, Rene shouts.

The executioner abandons

the spot above, to start

cutting, with a small knife,

into the thick of the throat

underneath, inching the blade

through the feeling flesh, alive.

The wind and the bellows

wrestle into the leaves

above us. More warm dung drops

to the ground. The vocal cords

get cut. A last gurgling hiss…

He can no longer voice what he feels.

Shut in. Further removed.

Hung by the horns, the great

black body slumps and kneels

to the live tree. The last

that the bull sees is not

this immaterial blue,

a tropical Easter Sunday sky,

but his own red blood’s swamps.

The crowd cheers.

Haiti, April 1993

(All extracted from Crossroads and Unholy Water, Southern University Press, USA, 2001. See the review of the book, in Creole, by Takodo)

Saint Ursula’s Passion —by Marilène Phipps

Poems by Tontongi

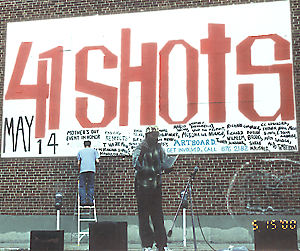

Ballads For The Killing of Diallo

(dedicated to Amadou Diallo who, in 1999, was fatally hit nineteen times by forty-one bullets shot by four New York City cops)

Tontongi reading this poem on May 14th, 2000

Diallo died at the frontal

of his house a certain night

his smile survived intact

amidst pierced arteries

body showered in blood

but peaceful as a yoga’s siesta.

The four policemen were blown

in an ecstasy of bang! bang!

claiming masculinity in terror;

the beauty of their guns

the perfection of the fire power

the gymnastic glory of their move,

quick, precise, mathematical

enhanced by the poetry of the night

had avenged all that was lost

but thrived to be regained;

regained was the purity of the race,

calm security trust and repos d’esprit.

Diallo died one night

for the salvation of the land

for the grace of the Stock Exchange

but his village was mourning

his passing on a distant universe

they shed tears for his going away

from his mother’s matrices

and his premature return to ashes.

The goods he sold were his mantra,

forced entry by sacrificial means

in the sanctum of all-market USA;

he was an angel of delusion

a real brother from the Bronx.

Had they known each other

Diallo would tell Abner Louima:

brother in blood and cry

the non-sense has a sense

eternal purgatory

of an ever-unreachable Promised Land

heading to a fake heavenly splendor

the guns won’t stop

but all will still be there.

Had the killed met his killers

instead on the somber New York street

in a carnival in Rio or in Port-au-Prince rara

together virile and deflated

burst by the Ogoun’s fervor

joyful in carnal delirium

blessed and bathed in the animal sweat

Thanatos and Eros in fusion

living a last rite to life

they would surely be friends.

They would say to each other,

co-bacchanals in before-death ecstasy:

“we are all pawns in a global madness —

let’s celebrate the fugitive moment.”

And the violence of the lost time

gave way to a new day of light,

spleen, stress, blues, nightmare,

white fear and black distress

were relocated to Nothingness’ trashes

the village cried one last time

its conscience was now its only respite.

On the first day of the trial

as a last sacrificial offering

the people had demanded the hanging

for mayhem of the four vicious policemen

the rich cried their loss of safety net

and the poor the continuing hell.

But the jury handed to the Diallo’s killers

the medal of valor for their sense of danger.

Diallo’s death saved the day,

sad day.

The last poem

(dedicated to Aldo Tambellini)

I shall write a poem that will tell it all,

sing the nightingale’s nightly song,

penetrate the labyrinth deep inside,

unveil its mystery’s inner soul.

I shall turn on the light

and open up the doors and the ceilings

to the immense oversight of infinitude;

I will tell Cedye’s story

his slow pace to the martyrdom’s state

where his spirits were lost to Aganman.

I will tell how Marie Lagone was defeated

and ceded to the worms never again

to regain her glory in our world.

My poem will revisit Ti-Gerard painting

the belly of the Beast with beautiful colors;

I shall make it a Pantheon from Hell,

the twist in the depth of quiet indifference

toward a destiny made to cry alone

yet screaming to help the baby from dying.

I will tell the travails of Magdalena, proud Amazon

losing her universe on a flip of a dice, here and there

there were losses because no one was there to help

reinvent our cosmos anew;

there was suffering all over.

When Hell governs the celestial values

our empty frailties are gone to the abyss;

I will tell what it was that went wrong,

reenact the primal nurturance of the land

before Good-Feet killed himself on a binge;

I shall tell what should never be told.

My poem will tell my story

both my glories and my pains;

I will tell my nocturnal wonderments

my lonely rêveries at the Saint Andre Park

behind the eerie colossal shadow

of the Reims Cathedral;

I will tell my love for Christina

the beauty once lived before Armageddon;

I shall tell of my youth consumed by my dreams.

My poem must reveal the horrifying

degeneration of life toward irrelevance;

I shall tell why all looks so normal

in so dimmed everyday life’s nightmare;

I will tell the loss by my country

of its nutrients, eroded from its roots;

I will sing and curse all the same

the serial death of my brothers and sisters

sacrificed to the altar of natural selection,

murdered by Haiti’s murderous poverty;

I shall tell the unfairness of their fate.

I shall write the ultimate poem

the silent cry of the Zebra’s complaints,

the trap of the vast multitude

within the infernal coercion of exploitation;

I will tell the alienation of the policeman

whose gun is a curse dreaded by his own conscience,

perishing in the Great Void of Contingence;

I will sing a song,

a simple melody for the no man’s land.

My poem will be made of tears

for those who have no more left to shed;

I will tell what happened to Michel

crossing his entire youth’s path from

running to running for his life

until he was found dead at midday

no one ever knew what his story was.

I shall tell of my purgatory

just like Mumia Abu Jamal told of his sojourn in hell;

I shall tell of the police brutality victims suddenly

transformed to Attila the Hun to cover the mayhem.

I shall tell of the banning of poetry in State affairs;

I shall tell The Amadou Diallo’s story

the Louima’s and Dorismond’s stories,

I will tell it all in one verse.

My poem must expurgate my manhood

unveil the animality of the best of my being,

reveal both the monster behind the friendly smile

and the humanity of my most evil deeds;

I shall undress the species to its pure nudity,

relegate our vanity to the dustbin of time;

I shall tell a new story.

I shall write a poem that will destroy it all

the beauty as well as the ugliness

the love as well as the hate;

my poem will start from the scratch

from the point where nothing is cursed or blessed

from the point of total innocence.

I shall write a poem that incites a global destruction,

a new Big Bang giving way to a new nothingness,

an original feast where all splendors are there,

there, at easy reach to the human frailties.

I shall write a poem anti-poem

a poem that will not be read to the king,

a poem for all that is not there and should be.

I will write a poem to cry,

cry the waste, the losses and the non-sense;

I will write a poem to tell you I was there

in blood and in flesh witnessing both the calvary

and the great potentials for a work of beauty;

I shall write a poem for happiness

the kind only kindred spirits have experienced;

I shall write a poem just to be.

I shall write a poem for only the pleasure

I extract from my state of total freedom,

for the ecstasy in conquering evanescence;

I will write a poem for the glory

from the smile of a beautiful child;

I will write a poem to celebrate the cerebral,

and yet subliminal cadence of the sexy gal

crossing the street with celestial wisdom

mixed with sweat, blood, contemplative sins.

I will sing the freshness of the dawn,

the sun’s majestic and ever peaceful sleep,

the pubertal elegance of the spring roses,

I will sing the beauty that is already there.

The poem I will write

will be hurting inside and boasting outside

just like my life has been;

it will radiate of the multiple splendors of the spleens,

turning the drought to a generous spring

and the desert of hell to a fertile Eden;

my poem will embrace the Grand Canyon,

recompense the artist’s inner pace,

and plant flowers along the lonely road.

I shall write a poem that will end it all,

all that contributes to the engine of hell;

I shall write a poem just to say nothing,

simply to be there.

I shall write a poem to destroy poetry

and put in its stead a big proclamation:

No more unnecessary death

No more anti-woman testosterone

No more Wall Street speculation

No more bosses that boss people around

No more bastards who hate life

No more rich people that live off poor people

No more whites that kill blacks

No more blacks that kill whites

No more schools that produce dummies

No more idiots with a license to be idiot

No more superwomen that become hyperbitch

No more misogynous heroes

paternalist monsters

libido destroyers

No more abusers of children

No more people who choose death over life

No more zombies aiding zombie-makers

No more innocent people in death row

No more refugees dead in high seas.

I will write a last poem

a poem of love

a poem for you to read

a poem that will tell who we are

I will write a poem

to incite multiple impulses

a Big Boom of creative happenings,

a renaissance since the primal vision.

—Tontongi Boston, February 1999

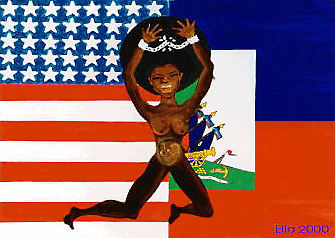

Poems by Ella Turenne

The meaning of my feelings

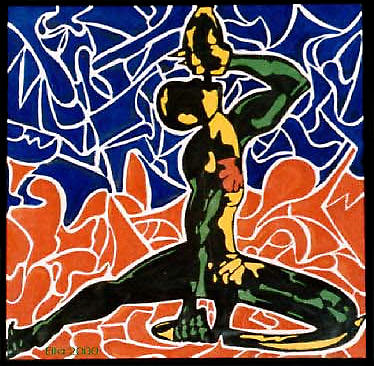

Riding. —by Ella Turenne

What is it like to be emotionally aloof?

To feel from the inside in,

imploding from the inability to convey emotion?

Like the opposite of emotionally amplified…

a comedy and tragedy

splitting sensations and sentiments.

You accuse me of being guarded,

and guiltily,

the impulses take control,

and before I know it there I am again,

whimpering,

denying vibes that are clearly

on the tips of tongues and

fronts of lobes.

Charged and submitting to

the unreal demands of emotional experiences,

my rational self isn’t strong enough to look past

the mistrust

the betrayal

the pain

that lingers from instances

of guised love.

What do you do with a busted heart

patched in all the right places,

flaunting all the right moves,

speaking with all the right vocabulary

once its old wounds are revived

at the moment of truth when

the genuine identity presents itself

only causing more rifts and deceit

rendering the receiver dubious of

potential motives and

said emotion?

I attest:

fronts protect a weak and worn heart

from extra baggage,

potential falls, and

supposed powerlessness.

How to hear that word

—love —

without trembling

from the anxiety,

from the thrill,

leaves me open,

confused,

and without sanctuary?

I, not wanting to be aloof,

am machined into the motions.

Reasons

Woman fleece. —by Ella Turenne

I can’t not be me.

Those who choose to be alive

and not live,

not take risks,

fail to discover themselves

and live with the mask

society has brainwashed us to believe.

I can’t not be black.

Breathe black.

See black.

Be black.

Mind, body, soul black.

Everyday

Black.

I can’t not be emotional.

Big,

No littles or subdues.

Sensations amplified to the 13th power.

Deep giggles.

Dense cries.

Bubbling with energy.

I can’t not be militant.

Living nightmares

engulfing my world

are enough to drown my optimism,

suffocate my passions,

scorch my dreams —

unless I self-revolutionize.

I can’t not be truth.

We’ve learned to live lies.

Recognize:

The truth will set you

a p a r t.

Knowledge is power.

Deception is the precursor to downfall.

Empowerment doesn’t lie in lies.

Neg Maron. —by Ella Turenne

I can’t not be Haitian.

The Pearl of the Antilles

is displayed on my skin

for everyone to see and celebrate.

A history rich and mixed

with struggles and joys,

pains and passions,

is lodged in the shell of my soul.

I can’t not be a womyn.

I will be seen, heard, remembered.

I will be mother, leader, daughter, inventor,

sister, healer, friend,

scholar, lover.

I am above, below, in front, in back, within.

Timeless.

Womyn I am—

with or without a man.

I can’t not be an artist.

The hits come every day.

The acceptance is rare.

The praise is scarce.

But,

the love from my soul

is infinite and

ever growing.

It’s how I be.

Why be black?

Think melanin.

Why be emotional?

Think LA riots.

Why be militant?

Think 41 shots.

Why be truth?

Think Tuskeegee.

Why be Haitian?

Think first black republic.

Why be womyn?

Think Nikki.

Why do black art?

Ain’t I black?

Don’t I do art?

Why be me?

Who do I know better?

—Ella Turenne

Poems by Doug Tanoury

Autumn In August

The unthinkable came to me

One night,

I felt her gone as a dream vanishes

Upon rising and gathers up its memory

In its wake.

Her touch is summer wind

In autumn trees,

A passing out of season,

Like leaves in August

Turning brown and crimson

And dropping off

On to still green lawns.

A thing out of step,

An order confused,

A long pattern of seasons

Broken and gone.

“She is not dead…

But only sleeping.”

I say out loud,

Certain that

Autumn cannot arrive in August,

As I make loud radio static

And breakers on the beach

By walking alone through dead leaves

That bury the grass gone dormant

In days of dark clouds

That sit on the horizon

Like cats on a window sill

In the zenith of twilight.

August

Late on these August nights,

I sit on my front porch

Unable to sleep,

And watch the stars,

But mostly I watch

The wind in the trees.

There is an elm a few doors down

That has branched out

Around the street lamp

So that the leaves glow

Translucent green in the night.

The wind moving branches

And leaves making it look

Like a carved jade sculpture

Come to life.

And I think that this has been

The summer of cut jade,

I have never seen grass so deeply green,

Or trees more ornate in their foliage,

And the sky has never been painted in

Finer shades of skyborn blues.

And I think too,

That this is what Icarus saw

And felt just before…

So if my wings fail now,

Let me fall, for I have kissed the sky

As if it were a holy icon

And filled my lungs with the

Pure whiteness of clouds, so

If I fall there will be no splash,

No sound except a sigh lifted

Airborne by the waves.

August Rain

I remember an August once

When I could talk to him

But didn’t and each word unspoken

Rested like a brick on the silence

That lay thick as a layer of mortar

And grew into hardness between us

These day’s I think of him

Mostly when rain falls in gray sheets

With a soft hiss as droplets

Paint the pavement with color

Of an overcast sky and collects

On the road in pools in brought to full boil

In summer storms with the

Sound of thunder on my skin

I recall in the air’s smell and

The wind cool in my hair

An August once when rain fell

In mortar gray hardness on our silence

August Leaves

Leaves of green

Foliage

Dancing lively and

Synchronized

In sunset skies

Sycamores in full

Silhouette

Are slowly changing

Magically

Transformed and stained

In subdued hues

Resembling

Weak tea tint

Evening’s

Watered down light

In sunset skies

Foliage

Dancing lively and

Synchronized

Leaves of green

Signs In August

As the mornings grow cooler in later August

I notice flowers grow more vivid

Each blossom wears a brighter shade

Each bud promises a more vibrant hue

And leaves grow a lusher green

In these evenings of late summer

The crickets seem to call louder

In a meter more pronounced

And becomes to me as I listen now

The very heartbeat of night

And in these signs I see

The season’s end foreshadowed

And I reflect on its last days

As rain falls in the afternoon and

Ends in white bursts across the pavement

Making leave and blossom twitch and tremble

As if animated the flowers awaken

From dreaming colors of summer mornings

And trees listen and sway silently to songs

That fill an August night

And I too am now awake

And wear a new more full awareness

Of the signs and signals of a season passing

And the significance of small and tiny symbols

Like a raindrop glistening

On a cricket’s charcoal back.

—Doug Tanoury

Poem by Marie-Hélène Laraque

To Find a New Land

To live my old dream

my homeland

to return to Haiti

to make a good life there

enjoy the weather and people

the plants and land

to bring something to my land

to see it thrive once again

to help the land be covered with

green again

to plant trees, food trees, flowers

to work with like-minded people

to bring new life to the old land

to be part of something worth-while

and good

to bring peace and to be a peace-maker

to help others to find a new way

a good path

to walk that path too

to know the heat and warmth,

the fog on the mountains,

the smell of the wet earth

my earth

my home

mine once again

in the home of my ancestors

To live my old dream

to know freedom

to live it

and accept it, and practice it

unchallenged by the endless choices

calm and sure and knowing

to others on my land

living their freedom too

in peace

and security

to feel truly secure

on every level.

To walk on my mountains

to discover the water places

in between the hills and the mountains

to walk into the cold water

feel the rocks under my feet

to walk among those rocks

pick watercress and mint

and feel my ancient people

with me

within me

and smile at the knowledge

and sureness of this.

To ride on horseback

in these mountains

and see for the first time

places I have wanted to see since childhood

the smells and tastes

of mountain-peoples’ food cooking

spit-out sugar cane, having

chewed it white, dry

sucking every drop.

To hear the old greetings of

the mountain people

as they pass each other walking

their Creole talk

the words and responses

I enjoyed so much as a child

feeling their connection

and mine.

To feel the connection

with the people

beyond our separations

and differences

our sameness, our spirit

our love

as it is given to me

each time.

To sleep there in the darkness

in the total blackness

but for the moon

and the candles

in the house of my childhood

up in the mountains

to rise and see the sun come up

through the mist

toes on wet grass

smells and sounds of home.

To know what to do with the land

to feel good about it

to plant it

to bring new life to it

to know it is well.

To know and accept my children’s

place there

or not

knowing they are well

and will be well

to be at peace there

to write and read

to rest

to walk

to know the silence

and the sounds.

To build something

a little caille in the traditional style

mud and sticks

and an earth floor to sit

and lie on

and a fire in the middle

to cook corn and coffee

and keep us warm

give us light and comfort

a knowledge of home

what it means to be alive

and a human being.

To bring encouragement and

new hope

to see my land used in a good way

thriving, green

to plant with my hands

gather, and share and eat

to know and understand the

things that grow

to know about the plants

and what used to be

to see how things are made—

baskets, earthen vase, djakout,

and where they grow—

tobacco, roucou, thyme,

seeds for necklaces.

To pick up flat stones

stones for carving

sea shells with holes in them

to wear in a sacred way

To see night fall

near the sea

palm trees

and the soft hot air

to breeze

the sun setting

the day is ending

the smell of the sea

the warm sand underfoot

the mountains in the distance

dark and full of mystery

the feeling—like nowhere else,

that painful beauty of home—

my beautiful land like nowhere else: Haiti.

—Marie-Hélène Laraque Boulder, Colorado, July 1997

Marie-Hélène Laraque passed away on March 30, 2000, at the age of 52. Anthropologist of profession, she devoted a big deal of her work to the cause of the rights of the indigenous peoples of the Americas, notably those of Canada’s Northwest Territories among whom she had lived during the last years of her life.

Marie-Hélène Laraque, April 1948–March 2000

In an eulogistic essay dedicated to her memory, her friend Marie Wilson painted a woman of action animated by a great passion for life. Reported Wilson: “As recently as a year ago [1999], through the Dene chiefs here in the Northwest Territories, she arranged for the National Assembly of First Nations [an assembly of indigenous chiefs] to pass a motion recognizing a 1533 treaty between a hereditary Taino Chief, Guarocuya (Cacique Henri) and the crown of Spain. Through her motion, the Canadian chiefs recommended that a United Nations Special Report on Treaties and Agreements with indigenous populations around the world acknowledge this 1533 Bahoruco Peace Treaty as the very first treaty in the Americas between Indigenous people and Europeans.”

Further in the essay, Marie Wilson affirmed that Marie-Hélène was so much devoted to her activist work that one week before her death, still optimistic, she was making plans “to lobby on behalf of the dedicated health workers” she had met while undergoing cancer treatment: “She believed in the interconnections of people, and of our shared responsibilities to and for each other,” said Wilson.

As we feel in the internal music of her poem, she was manifestly the passionate for life depicted by her friend: “She had, said Wilson, ‘a smile that could light up a room, and a beauty that was inescapable.’”

Her poem, printed above, is a beautiful poem which waves its simplicity as a badge of honor, uniting the earth, its seed, life’s zest, and even life’s rubbish in a grand Whole, a sort of cosmic unity which would collapse without the continual renewal action undertaken every now and then by some of us.

It’s elating to see how the picture of her depicted by her friend, a Hélène generous of her time, “a caring and passionate sister to the world,” is vividly reproduced in the poem, like in the passage where she said she would like to return to Haiti to “enjoy the weather and people / the plants and land,” and further, “to bring encouragement and new hope / to see my land used in a good / way, thriving, green […] to know about the plants / and what used to be”.

“The death of my daughter Marie-Hélène was a blow that was devastating to me,” confided her father Franck Laraque, professor of literature at New York University, a well-known activist in the Haiti liberation movement. “She left Haiti when she was ten years old,” said Laraque, “to rejoin my wife and me in New York. She returned after the overthrow of the Duvaliers, more than thirty years later; but she had never forgotten the country of which she had retained a tenacious and luminous memory, as attested one of her poems written in English that I translated into French”.